For the past ten years, I’ve been studying genocide, especially those that appear in the wake of authoritarian regimes. The catalyzing force for this research is a novel that I’m writing about the generational impacts of the Holodomor. When I began writing this book, I had no awareness of the 1932 murder-by-hunger genocide that took the lives of seven to ten million Ukrainian people. Most people who ask me about my work don’t know about the Holodomor. This genocide was only acknowledged in America a few years ago, under President Obama, and its historical and traumatic connection to the current Ukrainian war is even less understood.

This is to say that on the day the latest war started, I was already thinking about violence and terror. We were in Italy, staying on an olive farm. My sister and her husband were with us. We read the headlines about Hamas and Israel from our phones, unable to fully grasp the cruelty and horror reflected there. We spoke of the mothers in all places of this world who are unable to protect their children from violence.

I remembered 9/11, one of the events that radicalized my peace activism, and brought me onto the streets to march against that war. Even at the buildup, there was little understanding in the U.S. of the pull toward counter-terrorism—America would invade Iraq and kill tens of thousands of people, and its government would be exploited by those who had always wanted a war in Iraq anyway. That last day in Italy, we read the news at breakfast, and I thought maybe this time, America would ask for the killings to stop, for civilians to be protected.

We drove back to the airport where we would fly to the next leg of our journey. There was so much quiet sorrow and then came news in a text that our longtime family friends had lost their son and brother, our childhood playmate, to cancer. We sent words to that grieving family because we could speak, because there were ones who could receive our condolences.

I kept thinking about the day before when my sister and I had been eating tiramisu and drinking cappuccino, and then lazing in the sun, laughing and telling stories about our younger selves while we listened to the bells on the donkeys in the field. There was some part of me that wanted to hold events to the time when I wasn’t aware of terror and its costs through racialized violence, state-sponsored bloodshed, fundamentalist ideologies, military dictatorships, police states, anti-colonial conflicts, contested homelands. I wanted a former state of innocence, one in which I relied upon being white, middle class, and welcomed home not to one but two countries.1

There’s inside me the one who loves to travel, who is sometimes the one who wants to adventure free from the weight of colonialist history. Before the latest war, I wanted to write you a newsletter about the joys of Greece, the swimming in the sea, the daily feta, the olives! [And I did have those experiences and I do write about them below.]

Wanting to be free of thinking about acts of terror is a luxury of white supremacist structures. Everywhere that we have been includes stories of oppression and revolution. Indeed, what I learn in each place on our journey is bound up in their beauty and their horror. There’s no alone out here, we are connected to the joy and suffering of the world.

I hear in my desire for being liberated by travel the urge toward justice, toward a world in which all people can move freely. I also want to have my knowing complicated. The two print books that I packed with me for this three-month trip through Europe were Timothy Snyder’s The Road to Unfreedom: Russia Europe America, and Anna Badkhen’s essay collection, Bright Unbearable Reality. I chose these books because they are nearly opposite in tone, but they each have at their center a story of moral complexity. They’ve pointed me toward deeper empathy than I can find on my own. I want to thank Snyder and Badkhen (who I had the pleasure of meeting in Banff,) for their adventurous, open-minded travels, and for speaking to a future in which humans might survive.

As always, art brings me to a home that we haven’t had through this time untethered to land or destination or former selves. Thank you to friends who have stayed in touch these past six weeks while we’ve been out here. We treasure your voices and feel your love.

And now, Ikaria.

Ikaria is an island thirty miles off the coast of Turkey, in the eastern Aegean. I ended up here because ten years ago, one of my doctors shared with me this story in the New York Times. This is the story of Stamatis Moraitis, who was 102 years old, and who had returned to his native Ikaria from the US in the 1970s after being diagnosed with cancer. He recovered with no sort of treatment aside from gardening, winemaking, and playing dominoes past midnight with friends — and proceeded to outlive all his American doctors.2

American media tended to focus on wellness and diet as the method toward happiness and a long life, but I was skeptical. What else was it about the Ikarian culture that brought them such resilience? A decade ago, I was breaking my body going too fast in a typical capitalist productivity myth and taking care of a man with a brain injury. When I learned that the island was a Blue Zone,3 which to some meant that Ikaria held the secrets of longevity, I was intrigued to see what that meant up close.

Despite many essays, books, and a Netflix special on the Blue Zones, I’m happy to report that Ikaria cares little about what the rest of the world thinks of it. Still rugged and wild, with unglamorous beaches, unpretentious food, simple architecture, few museums, galleries, and little nightlife (unless you count the seasonal festivals called panygiria,) Ikaria is beloved for what it remains despite our need for it to be otherwise.

First, Ikaria isn’t easy to get to, or out of. There are a couple of flights a day. We were delayed hours departing when the Athens military decided to run air exercises. Ferries from Athens leave at 7 a.m. and take six hours; overnight ferries take eleven hours. You might have to work to arrive there. That’s part of the adventure.

The first week after we arrived in Ikaria, I was still looking to go places and do things. Our adult child flew in to experience the first ten days with us, and they were beautiful company and a tremendous navigator on Ikaria’s winding roads with high cliff drops to the sea. We went to the best bakery on the island and ate baklava and chocolate cake. We watched people drinking espresso and playing backgammon in village cafes. We went to see a little church with gorgeous Byzantine designs. After a few days of visiting little villages in the hills, (and due to my anxiety about what seemed like treacherous driving,) we gave up the idea of visiting places, and I settled into a routine that went something like:

1. Wake up. Divination. Write (if my body felt like it.)

2. Make breakfast together. Dine on the porch.

3. Read.

4. Walk to the sea. Swim with the old people. Eat snacks.

5. Nap.

6. Walk to a dinner of traditional Ikarian favorites. Walk home.

7. Sleep.

Each day, like many of the Ikarians, we walked up the mountainous roads to the sea and back. Sometimes we ate our second meal at 4 pm and then gathered for a late night teatime. We had long, wandering conversations that could be picked up again after hours away from each other. Since most of our family gatherings had in the past been around holidays or events, the sense of expanded time, of interknit connection, of moving successfully through conflict, of imagining a shared vision, was significant. Doing less helped me discover this.

Ikarians live mostly outdoors. They eat a plant-based diet rich in wild herbs, vegetables, olive oil, and natural wine. Their communities are tight-knit, they go to festivals together, and they live multi-generationally. I heard stories of centenarians who had responsibilities for the home from their childhoods, working in the fields, tending olive groves, and hiking to the high mountain streams for water. They’re connected to their histories and their ancestors, and they’re also communal, with rich familial and political lives.

Ikaria is known as the “red rock,” proudly communist largely as a result of the Civil War in Greece (1946-49) when the island became home to 15,000 leftists, (at a time when the local population was just 11,000, so you can imagine the influence.) Greek poets, writers, composers, and academics were banished here. Ikaria is a stronghold of the KKE, the Communist Party of Greece, and the recent election made the second in line the social democrats. Communities prefer to raise their funds and determine their fate. In Christos in Raches, a police station was built decades ago but remains unused. Villagers felt that they could maintain public order perfectly well themselves, thank you.

Our family stayed near Evdilos at Kerame Studios, which has studio and larger apartments, a chapel, a communal pool, and a bar, as well as a restaurant with Ikarian food and a few things like toasties for the English. The owner is the son of the man who built the place, and they have added more apartments in his lifetime. Even the cleaners were second generation, women who had taken over the jobs from their mothers. An inexpensive apartment ($62/US/night including taxes) came with a minimalist kitchen that had a hot plate, a mini fridge, a sink, a few plates, and some utensils. I made a kind of Turkish coffee with a measuring tin and a strainer. We made one-pot breakfasts, and when we got tired of restaurants, pasta dinners. There’s a little market next door, where we bought honey and yogurt, $1.50 cans of beer, Ikarian lemonade, and incessant oregano crisps, and my partner went so often that he learned the owner’s story, and those of his family members.

An August visit with a loud scene of tourists will be unlike the experience that I describe here. Still, there are spring and autumn bargains on Ikaria. A friend stayed at Thea’s Inn in the off-season pre-Covid for $25/night.

You can live on Ikaria for less than in America, but the life isn’t for everyone. I’ll be including an interview with an Ikarian in my next post, for more insider information about this Greek island.

In Ikaria, there’s a free-thinking and creative identity. People rode motorbikes with their children and partners through the villages day and night, their loud mufflers became our morning alarm. Shopkeepers and hoteliers seemed to run their own hours, as they had them available. The food offered was what arrived on the island. No one stressed that a particular dish needed to look the same as it had the night before. The feral cats crooned around our seaside table for their next meal. When we were leaving, and couldn’t find the rental car owner, he sent word to leave the car anywhere we could park it at the airport and to toss the keys under the mat.

On Ikaria, I was surprised by the quickness with which my world became remote. This was initially uncomfortable, but then it settled into a kind of tender ache for less of everything. We had already given away half of what we owned, placed our things in storage, and were living out of a suitcase and a backpack. At times, I wanted more comfort and control, some luxe ice cream, and efficiency. I wished for fewer surprises. I wanted the island of my imagination, and not the one with garbage by the side of the road. By the end of the trip, I had begun to like not getting what I wanted. I joined the locals in getting naked at the tiny, perfect beach.

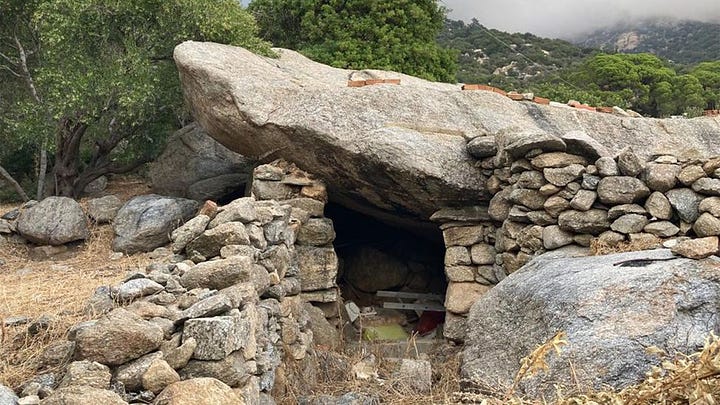

All over Ikaria, including a few steps from our hotel, we ran into stone houses with flat slate roofs, most of which were still standing, though with a crumbling wall or two. We learned that this was a strategy developed by Ikarians to avoid pirates overtaking their land. The Persian Empire, the Delian League of Greek city-states, the Romans, the Byzantine Empire, the Republic of Genoa, and the Knights of St John all exercised varying degrees of influence over Ikaria between 500 BCE and 1521 CE, at which point Ikaria fell firmly into the Ottoman Empire, where it would remain for more than three centuries. In Ikaria, this was a period of reclusiveness born out of conflict in the ‘century of obscurity.’ Turkish pirates drove islanders into the hills, hiding in chimney-less, windowless ‘anti-pirate’ houses, capped off by giant rocks that were the only thing visible from a distance. The BBC reports that “While piracy was first reported on Ikaria in the 1st Century BCE, it became a more-or-less unchecked threat during Roman rule and Byzantine rule. Then, after the arrival of the Genoese in the 14th Century, Ikarians resorted to destroying their ports to deter invaders. Even this act was not enough.” The Ikarians removed themselves into the island’s interior, where they built structures that from afar appeared to be boulders, slopes, and thickets so that ships out at sea noticed no signs of residence close to the shore. The "piratiki epochi" (pirate era) made the craggy mountainous interior the homes of Ikarian ancestors, and these places still exist today.

One day we arrived in a little village, parked, and set out to explore a few of the stone houses that lined the top of the mountains. Goats free-ranged over the land, farmers walked to their homes. A woman in an old truck passed us, pulled over, and called for us. She handed us armloads of red grapes, warm from the harvest. She told us to do something as she drove away, but we didn’t speak the language, so she pulled over again, got out of her truck, and showed us the communal water fountain where we could wash our fruits. Ef̱charistó̱! we shouted, pretty much the only word we knew in Greek—thank you! She waved and carried on. We felt like we belonged to this place.

More of what I’m thinking about:

Readers contacted me about my memoir being one of the 186,000 used to train AI for corporations like Meta without my consent after I posted about it on social media. This brilliant essay by Ted Chiang is one of the most thoughtful pieces on AI that I’ve run across. A necessary read for this era. Write me if you need to get past a paywall.

Next Time:

A month into our journey, I realized that I didn’t need to travel at all to find liberation. So why was I out here? Next time, I’m writing from a working olive farm in Italy.

You can find Sonya at~

The podcast I did with my kid.

I am a citizen of both Canada and the United States, perhaps the ultimate luxury is to have two places that will shelter you.

More than 30% of Ikarians live into their nineties, generally free from chronic illness and dementia, and many hit 100.

Ikaria is one of the Blue Zones — alongside Sardinia (Italy), which we’re also visiting on this trip. Others include Okinawa (Japan), Nicoya (Costa Rica) and Loma Linda (California).

As always, Sonya, you speak your heart and it touches others (like me) deeply. Living in an emotional state of horror and sadness, and desire to live in a peaceful and joyous moment...simultaneously...is exhausting. We keep trying to balance what is with what could be. Thank you for sharing your reality with us. Blessed journey!

Thank you for this in-depth post, Sonya. I resonated a lot with this beautiful sentence of yours: “but then it settled into a kind of tender ache for less of everything.” I have just started to read Dr Gabor Maté’s The Myth of Normal and it came to mind as I was reading about your thoughts on long life (and by extension how we’ve really got it all wrong over here). I look forward to your next update!