When a vacation goes awry.

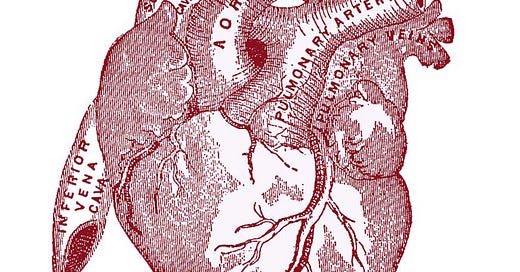

How a heart attack cancelled our trip to Berlin & placed us on another journey.

Two weeks ago I was up early writing this Wanderland newsletter declaring what our trip to Berlin was about, my finger ready to push the button on sending this image below out when . . .

. . . at 7:15 a.m., my partner Richard came into the living room pressing on his sternum and told me he had a strange pain in his chest.

“How long have you had this pain…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Wanderland to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.